Carbon Capture, Utilisation and Storage (CCUS) Potential in the Philippines

.jpg)

By Jesus T. Tamang, Former Director, Energy Policy and Planning Bureau, Department of Energy in the Philippines - ACN Advisory Member

7 February 2023

Note: Much of the information in this material is from the updated Philippine Energy Plan 2020–2040 and available materials from the Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia (ERIA).

The updated Philippine Energy Plan (PEP) 2020–2040 is set to support the country’s economic growth rate of 7.4% towards the end of the 2020–2040 planning period. During the period, electricity sales are expected to increase four-fold whilst total final energy demand is seen to post an annual increase of 5.8%.

The Philippines, whilst not a major greenhouse gas (GHG) emitter, is a signatory to the Paris Agreement and has submitted its Intended Nationally Determined Contribution (INDC) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). The country has also submitted its Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC), which aims to reduce the country’s GHG emissions by 75.0% by 2030 as an aspirational target compared with the business-as-usual (BAU) forecast. This comprises 72.29% conditional commitment and 2.71% unconditional commitment. Under the NDC, the energy sector remains the country’s major source of GHG emissions.

The PEP 2020–2040 presents how the energy sector intends to help achieve the county’s NDC through direct GHG reduction and GHG avoidance from renewable-based electricity generation. The sector’s GHG emissions only cover the combustion of fossil fuels and other activities related to the production of energy. The transport sector, whilst a major consumer of oil-based fuels, is treated separately with respect to GHG emission as the Department of Transportation, another government agency, is overseeing the sector.

Based on computed GHG, the energy sector can achieve a 2.8% reduction from 2020 to 2030, which includes both conditional and unconditional targets. This is equivalent to GHG emission reduction of about 45.9 metric tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (MTCO2e) or about 1.37% of the country’s NDC target.

Energy Policies

a. Policies

The overriding objectives of the PEP 2020–2040 remain towards energy security, resiliency, access, and affordability. A major statement in the PEP is its advocacy for the development and use of existing and emerging technologies in the most efficient and sustainable manner. In line with this, the updated PEP 2020–2040 has been formulated as a transformational plan favouring the adoption of clean energy fuels and technologies that they may dominate the energy sector even before the end of the planning period. Whilst there is no set policies yet on carbon capture, utilisation, and storage (CCUS), the identification of clean and emerging technologies is seen as a window for the possible entry and utilisation of CCUS.

b. Strategies

Critical to the success of the PEP 2020–2040 are the strategic focus areas that show how the energy sector will move forward to attain the envisioned clean and sustainable future. These include, amongst others, environmental management, pursuit for energy resiliency and security, continued energy engagements at the international front, and the collaborative role of the attached agencies.

The energy sector’s transition to having a clean and sustainable future is reflected in its supply and demand outlook, specifically under its clean energy scenario (CES). As shown by the PEP 2020–2040, the reference scenario (REF) will be the frontrunner to achieving the CES. The CES is an expanded scenario that provides for expanded use of renewable energy and other technologies, strengthened implementation of the Energy Efficiency and Conservation Act, the application of appropriate information and communication technologies (ICT) in the energy chain, and intensified implementation of energy resiliency.

The Energy Strategy

on Sustainable Path Towards Clean Energy

c. Energy Transition

The move towards attaining a just energy transition has compelled the energy sector to recalibrate its policies, programmes, strategies, and measures. The main objective of the transition is not the total elimination of fossil fuels but maximising the gains and benefits from renewable energy installations, energy efficiency and conservation, utilisation of clean alternative fuels for transport, and adoption of emerging energy technologies. With this backdrop, the sector will be steered on its path to creating a sustainable future that integrates climate change mitigation and adaptation strategies and supports the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), specifically on affordable and clean energy (SDG 7). Thus, during the period, we see the sector utilising new and advanced technologies, increasing capacity-building initiatives, and adopting innovative financing mechanisms.

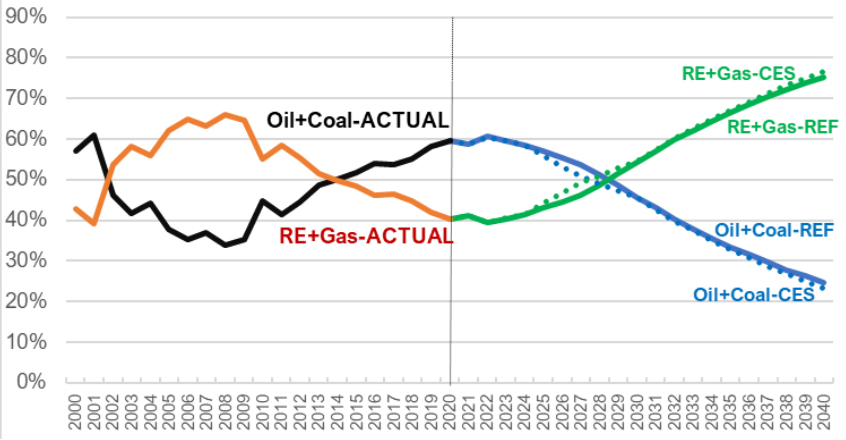

In this energy transition, the country’s power generation shifts from being coal-dependent to more diverse, with substantial contribution from renewables and natural gas. Natural gas is deemed the transition fuel that supports renewables-based generation. The mixed share of these clean energy resources reaches more than 75.0% of the total power generation in the CES by 2040. In the REF, the average share of fossil-fuel based (coal and oil) generation stands at 46.4% as compared with 54.0% of aggregate share of renewables and natural gas. As fossil fuels will continue to be utilised during the period, CO2 emission is expected to remain high although at a reduced level. The implementation of the moratorium on greenfield coal power projects is a factor in the capacity mix. The last coal projects added and considered are only those committed to be installed by 2025 in the REF and the CES.

The Power Generation Mix Resulting from Energy Transition

The Energy Mix of Power Generation Resulting from Energy Transition

With the perspective of having diverse power generation technologies aiding the transition and transformation, the energy sector does not discount the entry of new and other emerging technologies such as nuclear, hydrogen, and ocean thermal energy conversion. ICT will play an important role in the sustainable transition.

The strategy of environmental management and the programme towards energy transition can benefit and be hastened with the adoption of CCUS in the energy and industry sectors.

Role of CCUS in Achieving Carbon Neutrality by the Target Year

The PEP 2020–2040 presents the many programmes and projects designed and targeted to increase energy security and resilience, including the promotion of local clean energy—solar, wind, hydro, geothermal, and natural gas. These are expected to provide a bigger share of energy demand during the planning period, increasing the country’s energy security through energy self-sufficiency with consequent reduced requirement for imported energy.

Another PEP 2020–2040 programme promotes energy efficiency and conservation as a way of life to abate the need for increased energy supply and capacity.

The use of new and emerging technologies, which are assumed to more efficiently generate power, can reduce the need for imported and indigenous fossil fuels and even delay the need to install and invest in additional energy infrastructure.

Programmes and Projects of the Energy Sector that Contribute to CO2 Emission Reduction

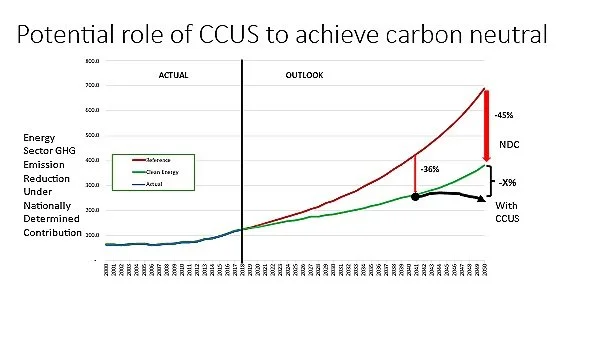

CCUS can enhance the CO2 emission reduction target of the whole energy sector, including of industry and manufacturing. CCUS will help achieve the goals for energy transition and a sustainable future.

With CCUS, the economy can benefit from accelerated achievement of the NDC commitment, more productive implementation of the Clean Air Act, additional investment for the required infrastructure, creation of new industries, and technology development.

CCUS Can Expand the CO2 Emission Reduction Beyond the Country's NDC

CCUS-related Activities

In 2013, the Asian Development Bank (ADB) published a report investigating the legal and regulatory frameworks for CCS in Indonesia, the Philippines, Thailand, and Viet Nam. The country studies mentioned that CCS legal and regulatory frameworks were not yet in place in the four countries at the time, except for some provisions for carbon dioxide-enhanced oil recovery. The Philippines study covered power plants south of Metro Manila and assessed the sufficiency of CO2 volumes for capture and reviewed geological data for storage capacity and potential storage sites in oil and gas fields. The study team analysed policy, technical, regulatory, financial, and public acceptance issues to address challenges in CCS deployment and came up with a road map for a CCS pilot project.

The study team recommended the establishment of a broad-based CCS working group within the government.

Recommendations

There appear to be benefits to implementing a CCUS project as it would support the many objectives and programmes of the energy sector, including achieving the NDC. As the benefits of CCUS are not limited to a particular country, perhaps the whole of ASEAN should have it in its set of actions for energy cooperation. ASEAN Member States need to be more active in available programmes and discussions on CCUS, such as those being conducted by ERIA.

The Philippines would do well to review its laws, rules, and regulations on oil and gas industry for possible adoption or extension to CCUS. It may be time to update the ADB study, considering the current and emerging technologies for implementing the CCUS project in either a centralised or distributed way. The update could be done by the recommended broad-based CCS working group within the government.